Over the last few months, I’ve been working with colleagues at Notre Dame to develop computational approaches we can use to identify the genres to which a literary work belongs. Initially, we focused our research on the georgic, a class of agricultural-cum-labour poems that flourished in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Eventually, though, our limited research corpus led us to investigate methods we could use to identify more period poetry, and these investigations helped reveal a fascinating if simple method one can use to identify poetic works in unstructured corpora.

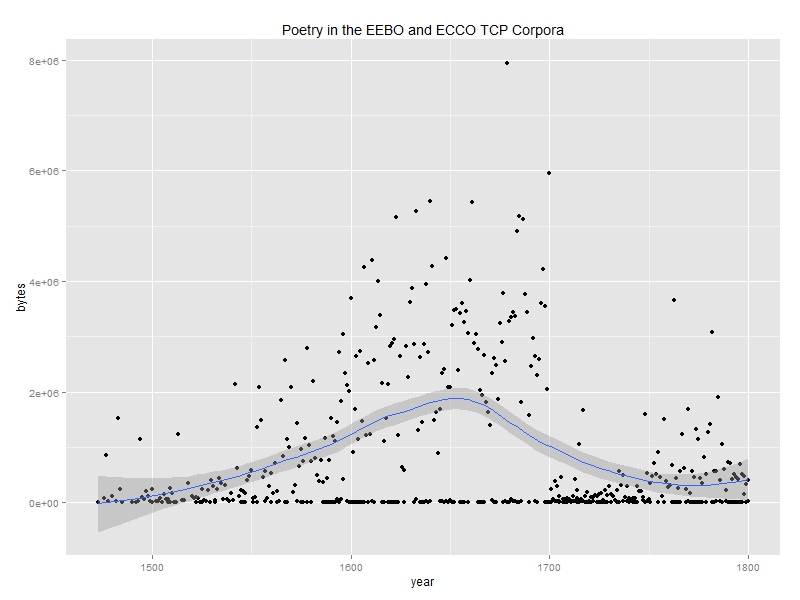

We began building our corpus of early modern English poetry by identifying the poetry curated by the Text Creation Partnership (TCP). Running a simple Python script over the TCP’s selections from the Early English Books (EEBO) corpus—which stretches from “the first book printed in English in 1475 through 1700”—and the Eighteenth Century Collections (ECCO) corpus, we extracted all the lines of text wrapped in <l> tags (the TEI designation for a line of verse). This left us with 16,571 text files, each of which contained only poetry from roughly the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries. After examining some of these files, we realized that many consisted entirely of poetic epigraphs, so we used another script to remove all of these small files (those smaller than 16 kb) from our research corpus, leaving us with a fairly substantive collection of poetic works from the period of interest:

Because the EEBO-TCP contains 44,255 volumes—roughly one third of all titles recorded in Alain Veylit’s ESTC data for the appropriate years—we felt reasonably confident that our holdings for the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were fairly representative of literary trends during the period. The ECCO-TCP, on the other hand, contains only 2,387 texts, less than one percent of ESTC titles from the eighteenth century. Even if we accept John Feather’s argument that only 25,131 literary works were written in English during the eighteenth century—11,789 of which, he claims, were poetic works—we are left to conclude that the 1,698 files in the ECCO-TCP corpus that contain poetry might not be indicative of poetic trends from the period. Given these conclusions, we were eager to supplement our collection of eighteenth-century poetry.

But where on earth can one find enormous quantities of eighteenth-century poetry in digital form? (This isn’t meant to be a rhetorical question; if you’ve got ideas, please let us know!) After considering the issue for some time, we elected to work with Project Gutenberg. Unfortunately, only after we had downloaded and unzipped all of the English files on Project Gutenberg did we realize that the enormous text collection (roughly 45,000 volumes) is all but entirely unstructured. We couldn’t find any master list of file names, author names, publication dates, or any other essential metadata fields, so we had to build our own.

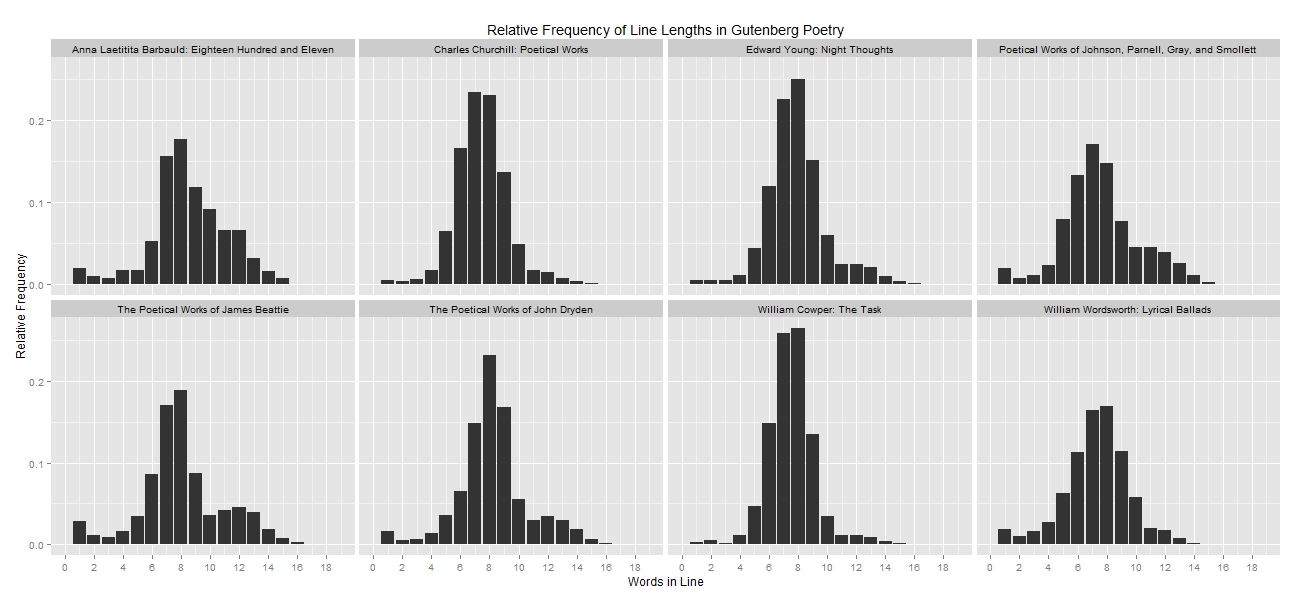

In the first place, we wanted to be able to differentiate poetic texts from non-poetic texts. While I imagine it would be possible to complete this task by analyzing the relative frequency of strings from each of these texts in the manner described in the previous post, we didn’t have reliable publication dates for the Gutenberg texts, so we needed an alternative method. Operating on the hypothesis that poetic texts have more line breaks and fewer words per line than prose works, we decided to measure the number of words in each line of each file. We then collected a random sample of poetic works to see what their words-per-line profiles looked like:

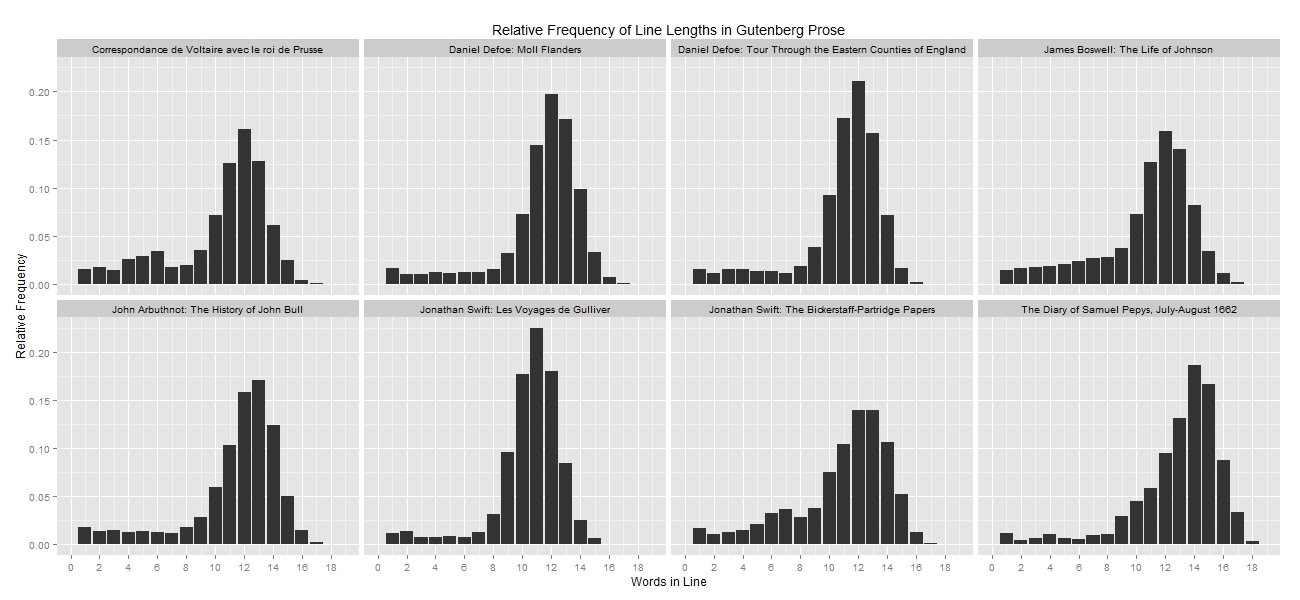

In these plots—each of which represents a single poetic text—the numbers along the x-axis indicate the number of words in a line of the text file, and the y-axis indicates the relative frequency of lines that contain such-and-such a number of words within the text. In The Poetical Works of James Beattie, for instance, only ~5% of lines had 12 or 13 words in them, whereas almost 20% of the text’s lines had 7 or 8 words in them. In other words, The Poetical Works of James Beattie is dominated by lines with seven or eight words in them, a fact that applies to all of the poetic works plotted above. With these figures in hand, we plotted the words-per-line profiles for a random assortment of prose works from roughly the same period:

We were pleased to see that these plots differed from the poetic plots quite dramatically! Comparing the two sets of curves, we see that poetic works contain a preponderance of lines with 7-8 words, while prose works contain a preponderance of lines with 11-12 words. This is naturally due to the fact that lines of text in prose works run across an entire page, while poets break lines strategically (and regularly in eighteenth-century verse). To identify poetry in unstructured corpora, then, we can calculate a text’s words-per-line profile, and use the results of those calculations in order to classify each text in our corpus as a work of poetry or a work of prose. Using a rather simple approach to the latter task, we found 3150 poetic works tucked in the Gutenberg corpus, a few hundred of which are from our period and can thus contribute to our study of genre classification.