Oliver Goldsmith, one of the great poets, playwrights, and historians of science from the Enlightenment, was many things. He was ‘an idle, orchard-robbing schoolboy; a tuneful but intractable sizar of Trinity; a lounging, loitering, fair-haunting, flute-playing Irish ‘buckeen.’’ He was also a brilliant plagiarist. Goldsmith frequently borrowed whole sentences and paragraphs from French philosophes such as Voltaire and Diderot, closely translating their works into his own voluminous books without offering so much as a word that the passages were taken from elsewhere. Over the last several months, I have worked with several others to study the ways Goldsmith adapted and freely translated these source texts into his own writing in order to develop methods that can be used to discover crosslingual text reuse. By outlining below some of the methods that I have found useful within this field of research, the following post attempts to show how automated methods can be used to further advance our understanding of the history of authorship.

Sample Training Data

In order to identify the passages within Goldsmith’s corpus that were taken from other writers, I decided to train a machine learning algorithm to differentiate between plagiarisms and non-plagiarisms. To distinguish between these classes of writing, John Dillon and I collected a large number of plagiarized and non-plagiarized passages within Goldsmith’s writing, and provided annotations to identify whether the target passage had been plagiarized or not. Here are a few sample rows from the training data:

| French Source | Goldsmith Text | Plagiarism |

|---|---|---|

| Bothwell eut toute l'insolence qui suit les grands crimes. Il assembla les principaux seigneurs, et leur fit signer un écrit, par lequel il était dit expressément que la reine ne se pouvait dispenser de l'éspouser, puisqu'il l'avait enlevée, et qu'il avait couché avec elle. | Bothwell was possessed of all the insolence which attends great crimes: he assembled the principal Lords of the state, and compelled them to sign an instrument, purporting, that they judged it the Queen's interest to marry Bothwell, as he had lain with her against her will. | 1 |

| Histoire c'est le récit des faits donnés pour vrais; au contraire de la fable, qui est le récit des faits donnés pour faux. | In the early part of history a want of real facts hath induced many to spin out the little that was known with conjecture. | 0 |

| La meilleure maniere de connoître l'usage qu'on doit faire de l' esprit, est de lire le petit nombre de bons ouvravrages de génie qu'on a dans les langues savantes & dans la nôtre. | The best method of knowing the true use to be made of wit is, by reading the small number of good works, both in the learned languages, and in our own. | 1 |

| Comme il y a en Peinture différentes écoles, il y en a aussi en Sculpture, en Architecture, en Musique, & en général dans tous les beaux Arts. | A school in the polite arts, properly signifies, that succession of artists which has learned the principles of the art from some eminent master, either by hearing his lessons, or studying his works. | 0 |

| Des étoiles qui tombent, des montagnes qui se fendent, des fleuves qui reculent, le Soleil & la Lune qui se dissolvent, des comparaisons fausses & gigantesques, la nature toûjours outrée, sont le caractere de ces écrivains, parce que dans ces pays où l'on n'a jamais parlé en public. | Falling stars, splitting mountains, rivers flowing to their sources, the sun and moon dissolving, false and unnatural comparisons, and nature everywhere exaggerated, form the character of these writers; and this arises from their never, in these countries, being permitted to speak in public. | 1 |

Given this training data, the goal was to identify some features that commonly appear in Goldsmith’s plagiarized passages but don’t commonly appear in his non-plagiarized passages. If we could derive a set of features that differentiate between these two classes, we would be ready to search through Goldsmith’s corpus and tease out only those passages that had been borrowed from elsewhere.

Feature Selection: Alzahrani Similarity

Because a plagiarized passage can be expected to have language that is similar but not necessarily identical to the language used within the plagiarized source text, I decided to test some fuzzy string similarity measures. One of the more promising leads on this front was adapted from the work of Salha M. Alzahrani et al. [2012], who has produced a number of great papers on plagiarism detection. The specific similarity measure adapted from Alzahrani calculates the similarity between two passages (call them Passage A and Passage B) in the following way:

def alzahrani_similarity( a_passage, b_passage ):

# Create a similarity counter and set its value to zero

similarity = 0

# For each word in Passage A

for a_word in a_passage:

# If that word is in Passage B

if a_word in b_passage:

# Add one to the similarity counter

similarity += 1

# Otherwise,

else:

# For each word in Passage B

for b_word in b_passage:

# If the current words from Passages A and B are synonymous

if a_word in find_synonyms( b_word ):

# Add one half to the similarity counter

similarity += .5

break

# Lastly, divide the similarity score by the n words in the longer passage

return similarity / max( len(a_passage), len(b_passage) )To prepare the data for this algorithm, I used the Google Translate API to translate French texts into English, the Big Huge Labs Thesaurus API to collect synonyms for each word in Passage B, and the NLTK to clean the resulting texts (dropping stop words, removing punctuation, etc.). Once these resources were prepared, I used an implementation of the algorithm described above to calculate the ‘similarity’ between the paired passages in the training data. As one can see, the similarity value returned by this algorithm discriminates reasonably well between plagiarized and non-plagiarized passages:

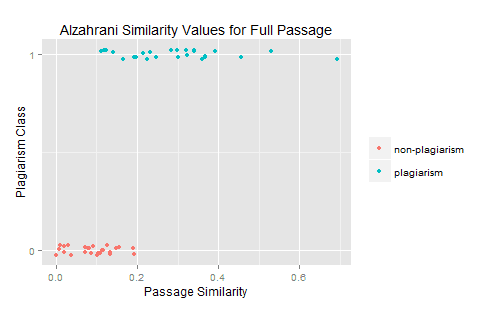

The y-axis here is discrete–each data point represents either a plagiarized pair of passages (such as those in the training data discussed above), or a non-plagiarized pair of passages. The x-axis is really the important axis. The further to the right a point falls on this axis, the greater the length-normalized similarity score for the passage pair. As one would expect, plagiarized passages have much higher similarity scores than non-plagiarized passages.

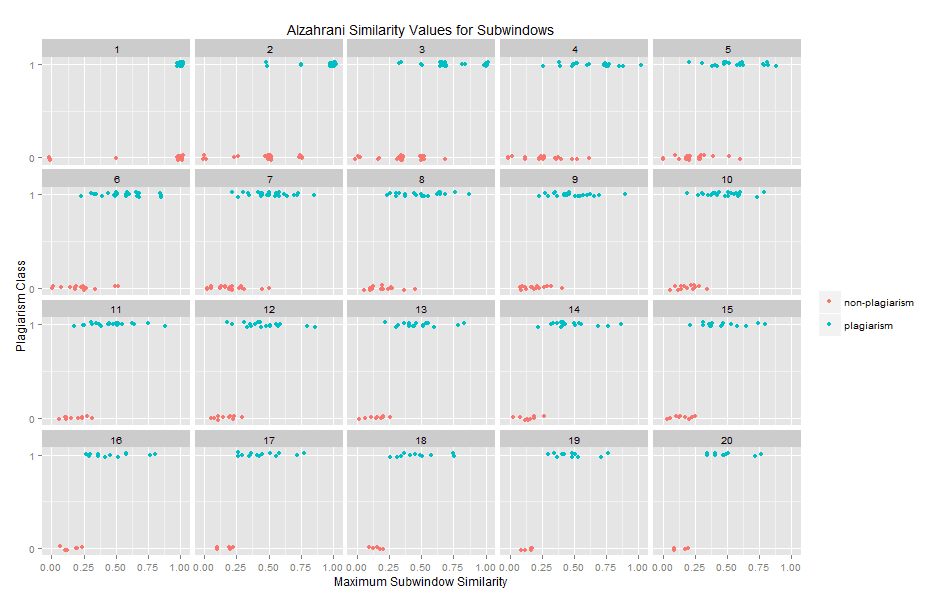

In order to investigate how sensitive this similarity method is to passage length, I iterated over all sub-windows of n words within the training data, and used the same similarity method to calculate the similarity of the sub-window within the text. When n is five, for instance, one would compare the first five words of Passage A to the first five from Passage B. After storing that value, one would compare words two through six from Passage A to words one through five of Passage B, then words three through seven from Passage A to words one through five of Passage B, proceeding in this way until all five-word windows had been compared. Once all of these five-word scores are calculated, only the maximum score is retained, and the rest are discarded. The following plot shows that as the number of words in the sub-window increases, the separation between plagiarized and non-plagiarized passages also increases:

Feature Selection: Word2vec Similarity

Although the method discussed above provides helpful separation between plagiarized and non-plagiarized passages, it reduces word pairs to one of three states: equivalent, synonymous, and irrelevant. Intuitively, this model feels limited, because one senses that words can have degrees of similarity. Consider the words small, tiny, and humble. The thesaurus discussed above identifies these terms as synonyms, and the algorithm described above essentially treats the words as interchangeable synonyms. This is slightly unsatisfying because the word small seems more similar to the word tiny than the word humble.

To capture some of these finer gradations in meaning, I called on Word2Vec, a method that uses backpropagation to represent words in high-dimensional vector spaces. Once a word has been transposed into this vector space, one can compare a word’s vector to another word’s vector and obtain a measure of the similarity of those words. The following snippet, for instance, uses a cosine distance metric to measure the degree to which tiny and humble are similar to the word small:

from gensim.models.word2vec import Word2Vec

from sklearn.metrics.pairwise import cosine_similarity

# Load the Google pretrained word vectors

google_dir = '../google_pretrained_word_vectors/'

google_model = google_dir + 'GoogleNews-vectors-negative300.bin.gz'

model = Word2Vec.load_word2vec_format(google_model, binary=True)

# Obtain the vector representations of three words

v1 = model[ 'small' ]

v2 = model[ 'tiny' ]

v3 = model[ 'humble' ]

# Measure the similarity of 'tiny' and 'humble' to the word 'small'

for v in [v2,v3]:

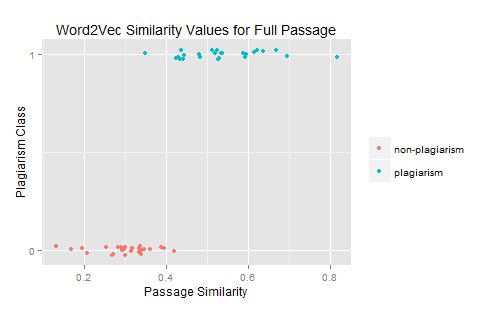

print cosine_similarity(v1, v)Running this script returns [[ 0.71879274]] and [[ 0.29307675]] respectively, which is to say Word2Vec can recognize that the word small is more similar to tiny than it is to humble. Because Word2Vec allows one to calculate these fine gradations of word similarity, it does a great job calculating the similarity of passages from the Goldsmith training data. The following plot shows the separation achieved by running a modified version of the ‘Alzahrani algorithm’ described above, using this time Word2Vec to measure word similarity:

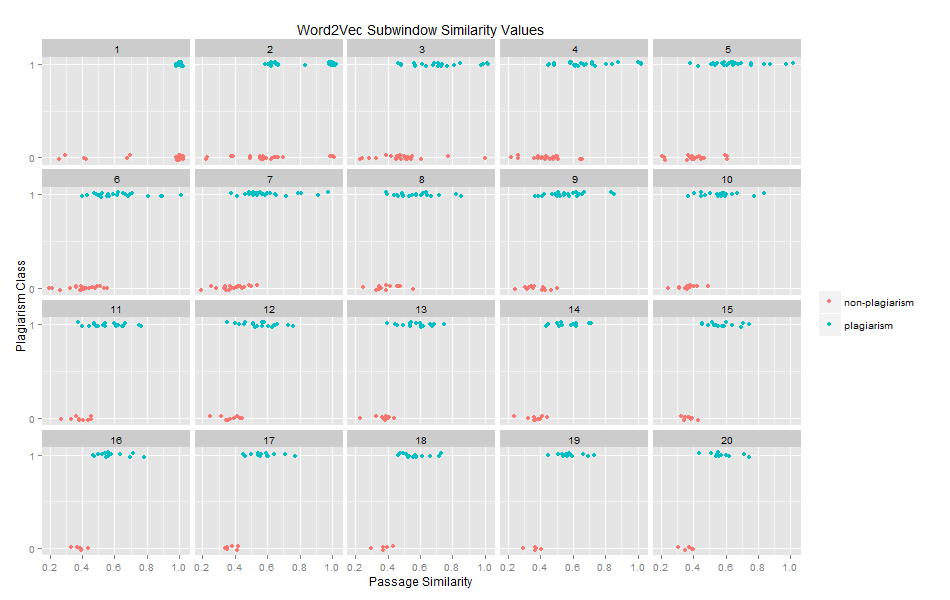

As one can see, the Word2Vec similarity measure achieves very promising separation between plagiarized and non-plagiarized passage pairs. By repeating the subwindow method described above, one can identify the critical value wherein separation between plagiarized and non-plagiarized passages is best achieved with a Word2Vec similarity metric:

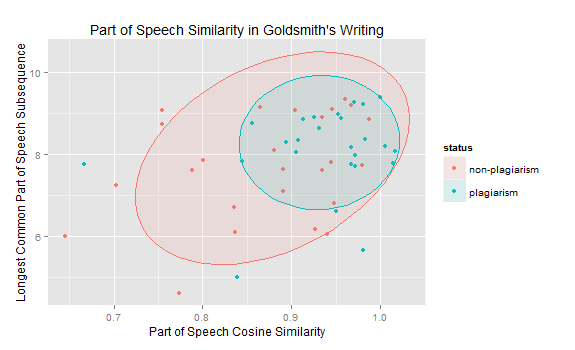

Feature Selection: Syntactic Similarity

Much like the semantic features discussed above, syntactic similarity can also serve as a clue of plagiarism. While a thoroughgoing pursuit of syntactic features might lead one deep into sophisticated analysis of dependency trees, it turns out one can get reasonable results by simply examining the distribution of part of speech tags within Goldsmith’s plagiarisms and their source texts. Using the Stanford Part of Speech (POS) Tagger’s French and English models, and a custom mapping I put together to link the French POS tags to the universal tagset, I transformed each of the paired passages in the training data into a POS sequence such as the following:

[(u'Newton', u'NNP'), (u'appeared', u'VBD'),...,(u'amazing', u'JJ'), (u'.', u'.')]

[(u'Newton', u'NPP'), (u'parut', u'V'),...,(u'nouvelle:', u'CL'),(u'.', u'.')]Using these sequences, two similarity metrics were used to measure the similarity between each of the paired passages in the training data. The first measure (on the x-axis below) simply measured the cosine distance between the two POS sequences; the second measure (on the y-axis below) calculated the longest common POS substring between the two passages. As one would expect, plagiarized passages tend to have higher values in both categories:

Classifier Results

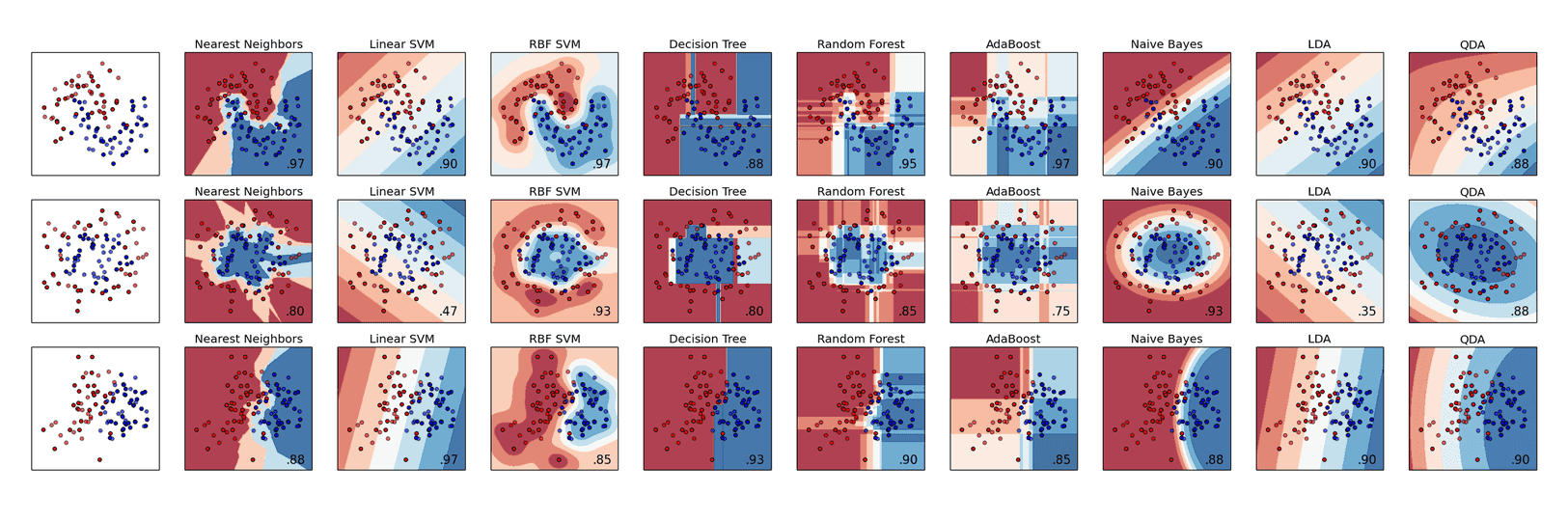

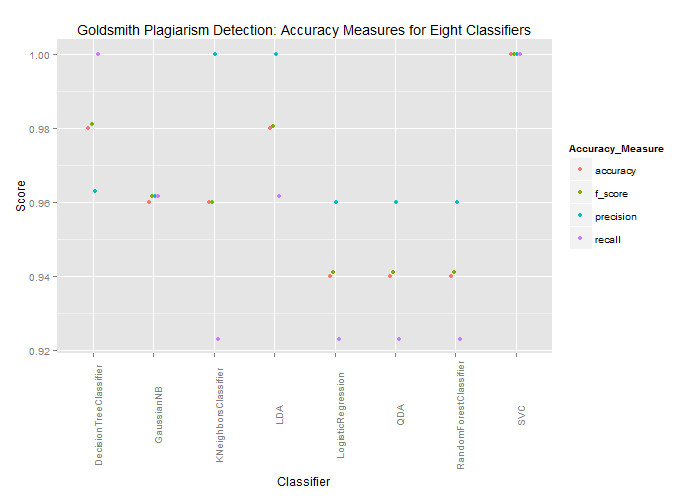

From the similarity metrics discussed above, I selected a bare-bones set of six features that could be fed to a plagiarism classifier: (1) the aggregate ‘Alzahrani similarity’ score, (2) the maximum six-gram Alzahrani similarity score, (3) the aggregate Word2Vec similarity score, (4) the cosine distance between the part of speech tag sets, (5) the longest common part of speech string, and (6) the longest contiguous common part of speech string. Those values were all represented in a matrix format with one pair of passages per row and one feature per column. Once this matrix was prepared, a small selection of classifiers hosted within Python’s Scikit Learn library were chosen for comparison. Cross-classifier comparison is valuable, because different classifiers use very different logic to classify observations. The following plot from the Scikit Learn documentation shows that using a common set of input data (the first column below), the various classifiers in the given row classify that data rather differently:

In order to avoid prejudging the best classifier for the current task, half a dozen classifiers were selected and evaluated with hold one out tests. That is to say, for each observation in the training data, all other rows were used to train the given classifier, and the trained classifier was asked to predict whether the left-out observation was a plagiarism or not. Because this is a two class prediction task (each observation either is or is not an instance of plagiarism), the baseline success rate is 50%. Any performance below this baseline would be worse than random guessing. Happily, all of the classifiers achieved success rates that greatly exceeded this baseline value:

Generally speaking, precision values were higher than recall, perhaps because some of the plagiarisms in the training data were fuzzier than others. Nevertheless, these accuracy values were high enough to warrant further exploration of Goldsmith’s writing. Using the array of features discussed above and others to be discussed in a subsequent post, I tracked down a significant number of plagiarisms that were not part of the training data, including the following outright translations from the Encyclopédie:

| French Source | Goldsmith Text |

|---|---|

| Il n'est point douteux que l' Empire , composé d'un grand nombre de membres très-puissans, ne dût être regardé comme un état très-respectable à toute l'Europe, si tous ceux qui le composent concouroient au bien général de leur pays. Mais cet état est sujet à de très-grands inconvéniens: l'autorité du chef n'est point assez grande pour se faire écouter: la crainte, la défiance, la jalousie, regnent continuellement entre les membres: personne ne veut céder en rien à son voisin: les affaires les plus sérieuses les plus importantes pour tout le corps sont quelquefois négligées pour des disputes particulieres, de préséance, d'étiquette, de droits imaginaires d'autres minuties. | It is not to be doubted but that the empire, composed as it is of several very powerful states, must be considered as a combination that deserves great respect from the other powers of Europe, provided that all the members which compose it would concur in the common good of their country. But the state is subject to very great inconveniences; the authority of the head is not great enough to command obedience; fear, distrust, and jealousy reign continually among the members; none are willing to yield in the least to their neighbours; the most serious and the most important affairs with respect to the community, are often neglected for private disputes, for precedencies, and all the imaginary privileges of misplaced ambition. |

| L' Eloquence , dit M. de Voltaire, est née avant les regles de la Rhétorique, comme les langues se sont formées avant la Grammaire. | Thus we see, eloquence is born with us before the rules of rhetoric, as languages have been formed before the rules of grammar. |

| L' empire Germanique, dans l'état où il est aujourd'hui, n'est qu'une portion des états qui étoient soûmis à Charlemagne. Ce prince possédoit la France par droit de succession; il avoit conquis par la force des armes tous les pays situés depuis le Danube jusqu'à la mer Baltique; il y réunit le royaume de Lombardie, la ville de Rome son territoire, ainsi que l'exarchat de Ravennes, qui étoient presque les seuls domaines qui restassent en Occident aux empereurs de Constantinople. | The empire of Germany, in its present state is only a part of those states that were once under the dominion of Charlemagne. This prince was possessed of France by right of succession: he had conquered by force of arms all the countries situated between the Baltic Sea and the Danube. He added to his empire the kingdom of Lombardy, the city of Rome and its territory, together with the exarchate of Ravenna, which were almost the only possessions that remained in the West to the emperors of Constantinople. |

| Il n'est point de genre de poésie qui n'ait son caractere particulier; cette diversité, que les anciens observerent si religieusement, est fondée sur la nature même des sujets imités par les poëtes. Plus leurs imitations sont vraies, mieux ils ont rendu les caracteres qu'ils avoient à exprimer....Ainsi l'églogue ne quitte pas ses chalumeaux pour entonner la trompette, l' élégie n'emprunte point les sublimes accords de la lyre. | There is no species of poetry that has not its particular character; and this diversity, which the ancients have so religiously observed, is founded in nature itself. The more just their imitations are found, the more perfectly are those characters distinguished. Thus the pastoral never quits his pipe, in order to sound the trumpet; nor does elegy venture to strike the lyre. |

Conclusion

Samuel Johnson once observed that Oliver Goldsmith was “at no pains to fill his mind with knowledge. He transplanted it from one place to another; and it did not settle in his mind; so he could not tell what was his in his own books” (Life of Johnson). Reading the borrowed passages above, one can perhaps understand why Goldsmith struggled to recall what he had written in his books–much of his writing was not really his. As scholars continue to advance the art of detecting textual reuse, we will be better equipped to map these borrowed words at larger and more ambitious scales. For the present, writers like Goldsmith offer plenty of data on which to hone those methods.

This work has benefitted enormously from conversations with a number of others. Antonis Anastasopoulos, David Chiang, Michael Clark, John Dillon, and Kenton Murray of Notre Dame’s Text Analysis Group, and Thom Bartold, Dan Hepp, and Jens Wessling of ProQuest offered key analytic insights, and Mark Olsen and Glenn Roe of the University of Chicago’s ARTFL group shared essential data. I am grateful for the generous help each of you has provided. Code is available on GitHub.