Suppose you have a collection of text files and would like to compare each of those files to each of the others. Perhaps you would like to know which characters, locations, or stage directions in each file occur in any of the others. Whatever the task, if your collection is small enough—on the order of a few paragraphs, say—you can of course compare the files manually, reading each of your paragraphs in turn, and comparing the given paragraph to each of the others. If your collection is a bit bigger—on the order of a few hundred novels, say—you might automate these comparisons on your computer. If your collection is really big, however, a single computer might not be powerful enough to finish the job during your lifetime.

Comparing each file in a four text corpus to each of the others, after all, only involves six comparisons. Running the same analysis on a collection of 50,000 files (roughly the size of the Project Gutenberg collection in English, or the EEBO-TCP corpus), however, means running 1,249,975,000 comparisons. If each of those comparisons takes one minute to execute on your computer, it will take 2376 years to run this job on your machine. Thankfully, we can expedite this process tremendously by leveraging the power of distributed computing systems like Sun Grid Engine (SGE) queues. Pursuing the routine described above, for instance, we can use an SGE system to run each of our 1+ billion comparisons in a few minutes.

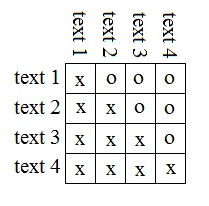

To get started, we’ll want to create an ‘iteration schedule’ in which we identify all of the comparisons we wish to run. Here is a visual representation of an iteration schedule for a four text corpus:

In the table above, each of our iterations-to-be-run is denoted by an ‘o.’ Each ‘o’ sits in the cell that joins the row and the column that denote the two texts to be analyzed in the given iteration. Reading across our first row, for instance, we see that text one does not need to be compared to text one, but does need to be compared to texts two, three, and four. The second row denotes that we want to compare text two to texts three and four, and row three denotes that we want to compare text three to text four.

After determining all of the comparisons to be run, we will want to render that information in machine-readable form. More specifically, we want to generate a table that has three columns: iteration_number, first_text, and second_text: where first_text and second_text are the file names of the two texts we wish to compare in the given iteration, and iteration_number is an integer whose value is zero in the first row of the iteration schedule, 1 in the next row, 2 in the next, . . . and n in the last, where n equals the total number of comparisons we wish to make. In general, the number of comparisons required is (p-1)(p)/2, where p equals the number of files in your corpus. Here is a sample iteration table:

0 A00002.txt A00005.txt

1 A00002.txt A00007.txt

2 A00002.txt A00008.txt

3 A00002.txt A00011.txt

4 A00002.txt A00012.txt

5 A00002.txt A00013.txt

6 A00002.txt A00014.txt

7 A00002.txt A00015.txt

8 A00002.txt A00018.txt

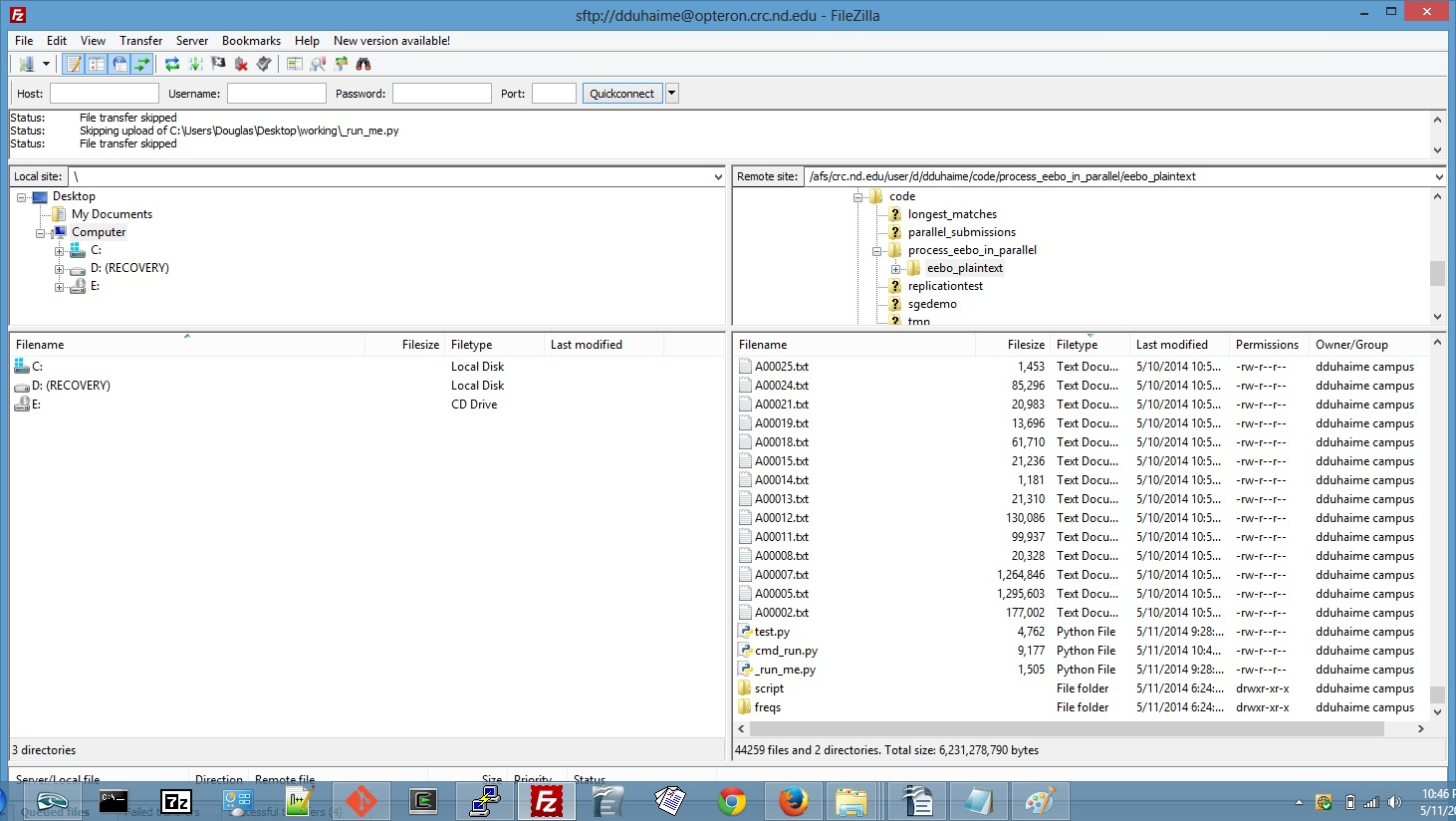

9 A00002.txt A00019.txtIf you want to batch process a different kind of routine on an SGE system, you can modify your iteration schedule appropriately. If you only want to calculate the type-token ratios of each of your files, for instance, you’ll only need two columns: iteration_number and text_name. Once this iteration schedule is all set, we can turn to the script to be run during each of these iterations. Here’s mine: If you want to run a different kind of analysis, just keep lines 1-21 and line 102 of that script, and use the variable “iteration_number” to guide which texts you will analyze in each iteration. Once your routine is all set, save it as “test.py” and upload it—along with your iteration schedule, the files you wish to compare, and these two—to a single directory on your SGE server:

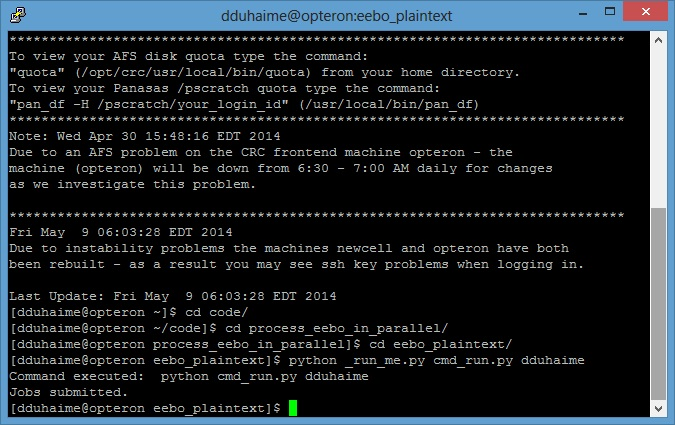

Once all of these files are in the same directory, you are ready to submit your script for batch processing. To do so using the University of Notre Dame’s Center for Research Computing system, you can simply type python _run_me.py cmd_run.py your_netid:

After you submit this command, the higher-order Python scripts _run_me.py and cmd_run.py will create new copies of your test.py script, changing the input files for each iteration according to your iteration schedule. If all has gone well, and you refresh the directory after a few moments, you’ll see a few (or more than a few, depending on the number of iterations you are running!) new files in your directory. More specifically, you’ll have a collection of new job files that give you feedback on the result of each of your iterations. If errors cropped up during your analysis, those errors should be recorded in these job files. Provided that there were no exceptions, though, those files will be empty, and you will find in your directory whatever output you requested in your test.py script. Et voila, now you can finish your analysis in a few minutes, rather than a few millennia!

I want to thank Scott Hampton and Dodi Heryadi of Notre Dame’s High Performance Computing Group, who helped me think through the logistics of batch processing, Reid Johnson of Notre Dame’s Computer Science Department, who sent me the higher-order SGE scripts on which this analysis is based, and Tim Peters, who wrote many of the Python modules on which my work depends!